Menu

Menu

Scales for Jazz Improvisation

I have played a lot of scales over the years. I mean a lot. One of the first things my father drummed into me when I was first learning piano, was to learn all my major and minor scales. I have done the same with every instrument I have played. On piano, I play these with each hand, and with both hands—in similar and contrary motion.

I even spent quite some time learning, and practising daily, all the modes of the major and minor scales. That, alone, equates to 252 scales! Yes, I’ve played a scale or two.

I’ll let you into a secret, though: I consider much of those hours, days, years a waste of time. Let me explain:

You see, doing all those scales gained me great dexterity and facility—which is not at all to be discounted—but I was under the impression that putting in all that work would help me become a better jazz player; that it would improve my improvising. It didn’t. It made me better at playing scales. I was working hard, but not being smart.

In a way, my working so hard, for so long, on those scales and modes was a form of laziness. It was easier to latch onto the magic bullet that I assumed I had found—that of hard daily work—than to really stop and think about that far more nebulous and overwhelming question: How do I actually learn to play jazz? It was a false path, and I took it.

“When you come to a fork in the road, take it” - Yogi Berra

Now, I’m not here to tell people that they shouldn’t practise their scales. Far from it. They are a crucial part of the learning process, and they should be learned. However, if you think they may be the gateway to improvisational skill, you’re wrong. Here’s why:

- This one is stating the obvious: listen to a good improvisor. They’re not playing scales. They may play snippets of scales, and even occasionally a complete scale, but it’s a small part of what they’re playing. (However, there are ways to still use scales, but avoid the trap of it sounding like one. More on this later.)

- Many people teach about chord/scale theory. For instance: For a minor seventh chord, you can play the second mode (dorian) of the major scale a tone (whole step) below the chord root. This is good to know, but it still leaves you with simply a scale. Now what?

- Major and minor scales and modes are asymmetrical. This is the big one. Let’s examine that further below:

Major and Minor Scales are Asymmetrical

One of the most important things an improvisor can do, is to state the chord changes. In fact, if you were to listen to a good solo without any accompaniment, you should be able to clearly hear the chord changes. This ability is so important, it has its own term. It’s called: “Playing the changes”.

How do we “play the changes”? Well, it turns out that there are some things that help to state the changes in our solos:

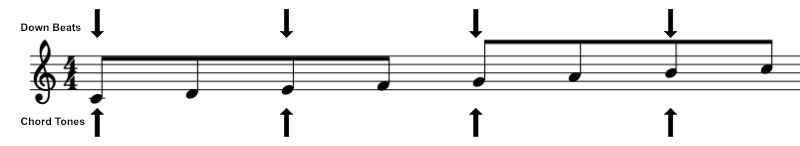

- Landing on chord tones on the down beats strongly states the chord.

- Thirds and sevenths are the most important notes to state the chord.

- When moving from one chord to the next a fourth above (C7 to F, for instance), the semitone (half-step) drop from the seventh of one chord, to the third of the next makes for a strong and pleasing line.

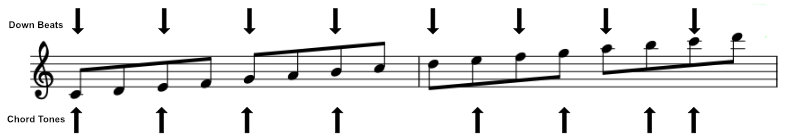

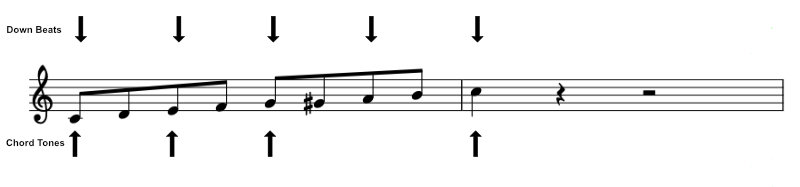

Let’s look at the first point, landing on chord tones on down beats, and take a look at an ascending major scale, played against a C Major Seventh chord:

It turns out that this works quite well. The down beats each coincide with a chord tone. Let’s extend it to two octaves:

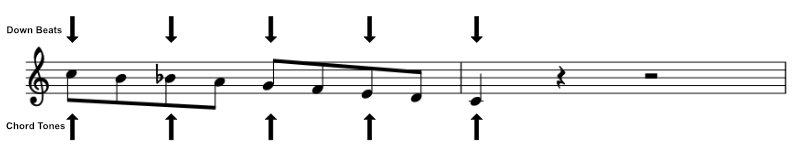

Oh dear. It seems to fall apart once we get into the second octave. Few of the chord tones come on a down beat. Let’s then look at the descending major scale played against a C Major Seventh chord:

Hmm. Things didn’t work out so well there either. Few of the chord tones land on a down beat. This demonstrates how regular scales are of limited use when “playing the changes”. If you use the scale—especially descending—few of the chord tones will land on the down beats. You would not be outlining the chord very well, and it would sound weak.

So, having firmly discounted regular scales as a vehicle for jazz improvisation, are there any scales which could be more useful? Yes! There are.

Bebop Scales

It’s not possible to know now what the thought processes of the bebop greats were. There were no jazz instruction books and most of their learning must have been simply through listening and emulation.

However, that doesn’t mean that rules, or norms, didn’t develop. One of the practices which emerged during this time neatly solved the problem of asymmetric scales.

Let’s take another look at the descending major scale against a C Major Seventh chord:

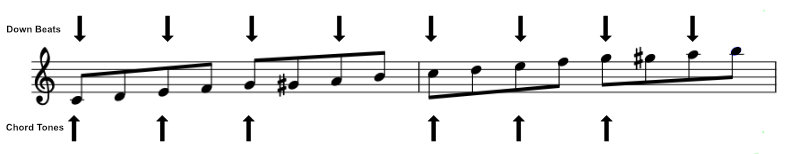

Few chord notes land on the down beats. As it happens, this scale can be made symmetrical simply by adding another note. We now have an eight note scale. Although any arbitrary note could be added, the note that is usually added to the major scale is the raised fifth (or flattened sixth). This is the major bebop scale, and it looks like this:

This scale is made up of the following degrees (ascending): 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, #5, 6 and 7. Now, every other note is a chord tone. The exception to this is the sixth, but the sixth is a consonant note and doesn’t really alter the essence of the chord (a sixth chord can be freely interchanged with a major or major seventh chord).

Furthermore, the addition of the extra note makes the scale work the same way ascending:

Finally, how about two octaves?:

We now have a very useful scale which guarantees that if we start on a chord tone, every other note will be a strong chord tone—whether played ascending, descending, or over octaves. I can see much more sense in practising this scale!

The Major Bebop Scale gives us a useful scale which can be played in whole, or in part, over all types of major chords (Major, Major Seventh, Sixth, Six/Nine). What about dominant chords though?

The Dominant Bebop Scale

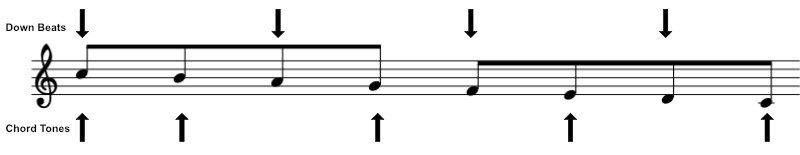

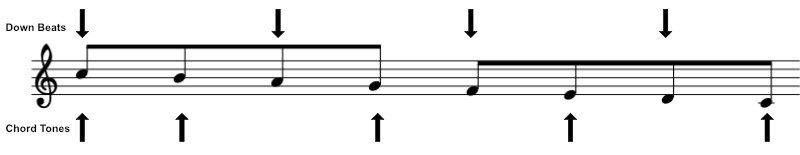

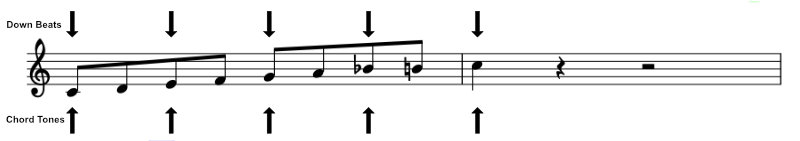

The scale for playing over dominant seventh and minor seventh chords is called the Dominant Bebop Scale, and differs only slightly:

The dominant bebop scale has both the minor seventh (the Bb in this case), and the major seventh (the B in this case). The scale degrees for this scale are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, b7 and 7.

As you can see, this scale is even better for outlining the chords, as every other note—every down beat—lands on a chord tone. And it works just as well descending:

You may have noticed that I said earlier that the dominant bebop scale can be played over a dominant seventh chord, and/or a minor seventh chord. Let’s revisit that by looking at the ubiquitous II-V-I:

In traditional chord/scale theory, it is stated that the same scale can be played over the entire II-V-I sequence. For instance, with a II-V-I in C (Dm7-G7-CMaj7), you can play the C major scale over the entire sequence. The technical explanation is that you’re playing the Dorian mode over the II, the Mixolydian mode over the V, and the Ionian mode over the I. The non-technical version is that you’re simply playing the major scale (the major scale of the I chord) over the three chords.

Now, let’s just take the first two chords in the sequence (the II and the V). If the same scale can be used over both of those chords, as explained by traditional chord/scale theory above, it follows that—as far as soloing is concerned—it doesn’t matter if both the chords exist or not. Whether the accompaniment is playing the II, and then the V, or is just playing the V, you can play over the same scale. In this case, the Dominant Bebop scale! Which one? The Dominant Bebop scale of the V chord.

Hopefully a couple of examples will make this clearer:

- G7-C. G Dominant Bebop over the G7, and C Major Bebop over the C.

- Dm7-G7-C. G Dominant Bebop over the Dm7 and the G7, and C Major Bebop over the C.

If you see a II-V-I, play the Dominant Bebop scale of the V over the first two chords.

Are there Minor Bebop Scales?

There are, and it turns out they’re “freebies”!

Do you remember from your basic music theory that each major key has a relative minor key? The relative minor is a minor third below the major. So, for instance, A Minor is the relative to C Major; C Major is the relative major to A Minor. Guess what? You already know the A Minor Bebop scale. It’s the C Major Bebop scale! Try it. It works!

Summary

Despite my countless years of playing major and minor (asymmetric) scales and modes, the Bebop Scales are the ones I practise the most now, and I encourage my students to do the same. They serve the same purpose of traditional scales in that they are a great physical exercise for fluency, but they also have the added benefit of giving you a foundation for improvised lines which guarantees chord tones landing on down beats—one of the fundamental requisites for “playing the changes”.

As these scales cover playing over major, minor, minor seventh and dominant seventh chords, you now have covered a huge majority of all the changes you will come across!

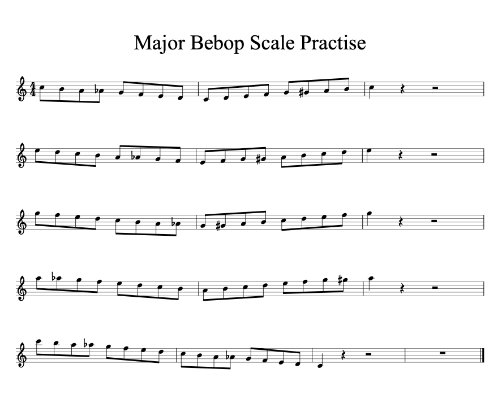

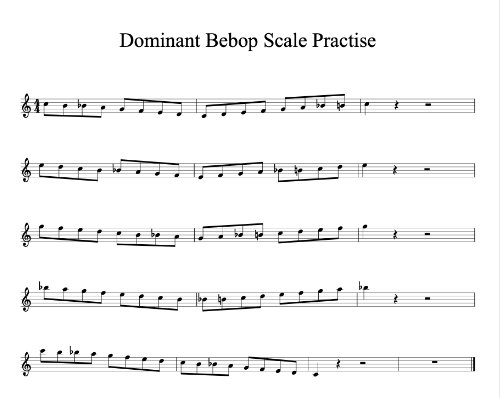

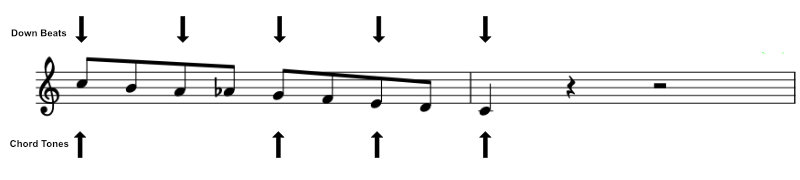

I’ll leave you with a couple of PDFs which outline how I practise the Major Bebop scale and the Dominant Bebop scale. I have written them in the key of C, but I encourage you to play them in all keys. Click on the images to download the PDF.

Bye for now!